You can’t believe how many different ways there are for a honey bee to die. Beekeeping is a life affirming activity that is often filled with death. Skunks and wild turkeys view bees as flying pieces of candy and will happily eat your bees as they fly from the hives. Mice and snakes try to make homes inside your hives, and the bees don’t care for this. Infections caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi abound. One particularly nasty bacterial infection called American Foulbrood is so deadly that a beekeeper must immediately destroy the diseased hive and burn the all their equipment so the infection doesn’t spread. As nasty as American Foulbrood is, it doesn’t top the list of threats to honey bees. Ask any beekeeper what enemy #1 is, and they will all say varroa mites.

Varroa mites are about 1/16″ and can be seen with the naked eye. They reproduce inside the capped brood. The mated female mites live on adult bees, and sometimes you can see the mites on the bees. Usually you won’t notice them in the hive, though. The mites weaken the bees and allow other diseases such as the Deformed Wing Virus to be introduced. Varroa mites can wipe out entire colonies. The mites happily co-exist with the bees during the summer months, but the mite population begins to increase at the end of summer at the same time the bee population begins to decrease in preparation for winter. Bees in fall and winter need to be strong in order for the colony to survive until spring. Varroa mites cripple the colony at the time when the colony needs to be the strongest. When the mites begin to overrun the colony, the bees will all leave the hive. This behavior is called absconding, and it is different from swarming. Swarming is a planned activity the colony undertakes to populate the world with more bees. Absconding is when the bees say, “It is so bad here, we need to leave because if we stay we will die.” Varroa mite infected colonies that abscond are referred to as mite bombs because they release varroa mites in the surround bee colonies and perpetuate rates of infection. Beekeepers who don’t pay attention to varroa mites in their colonies are like people who show up to a party with the flu and double dip their chip in the salsa bowl. It’s not a cool thing to do.

Last year, we treated our bees without even checking to see if they were infected. We just assumed they were infected since varroa mites are so prevalent. As first year beekeepers, we could only learn so many things at one time, and we didn’t want to have to learn how to test for mites. We just skipped the testing step and went straight for treatment. This year we tested one of our strongest colonies to determine if the bees were infected and if so what was the rate of infection.

Performing the test was mildly traumatic, but it provided lots of information. I used the standard alcohol wash test, which requires that you “sacrifice” (which is a nice way of saying “kill”) 300 bees. You take a frame of brood covered with bees and carefully check and re-check it to make sure the queen is not on that frame. You don’t want to accidentally kill the queen while testing for mites. You then shake the bees into a plastic tub. The nurse bees can’t fly yet and remain in the bottom of the tub. You tilt the tub and tap it on the ground so all the bees fall into a corner. Then you scoop up 1/2 cup of bees and place the bees in a receptacle that has an alcohol water solution. You swirl the bees in the alcohol until they die. What was pretty awful was that they didn’t die instantly. I opened the cap after the first few swirls and they were still trying to get out. I kept apologizing to the bees as I crammed them back into the jar where they would be killed with the alcohol. It had to be done. As Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk said after Spock exposed himself to a lethal dose of radiation in order to save the Enterprise, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Or the one.” As you swirl the bees, the varroa mites release from the bees and fall to the bottom of the jar so they can be counted. I was using a commercially available testing apparatus called the Varroa Easy Check by Veto-pharma. However, I have seen homemade apparatus with canning jars, screened lids, and buckets. Go to YouTube if you want to see how to make a homemade test kit. I paid ~$20 for my kit. I figured the test was important enough that I wanted to make sure I could perform it correctly, so I purchased a kit. The commercially available kit allows you to scoop the bees into a pre-measured basket that fits into a jar. The alcohol goes in the jar. After all the bees have died and their bodies have been swirled in alcohol for 1 minute, you lift the basket of dead bees out of the jar. The mites are left in the bottom of the jar, and you can count them. If this all seems too confusing, you can go and watch videos of the test on You Tube. I was limited on the pictures I could take. The surviving bees were mad and kept trying to sting me, so I couldn’t get my hands out of the gloves to take pictures.

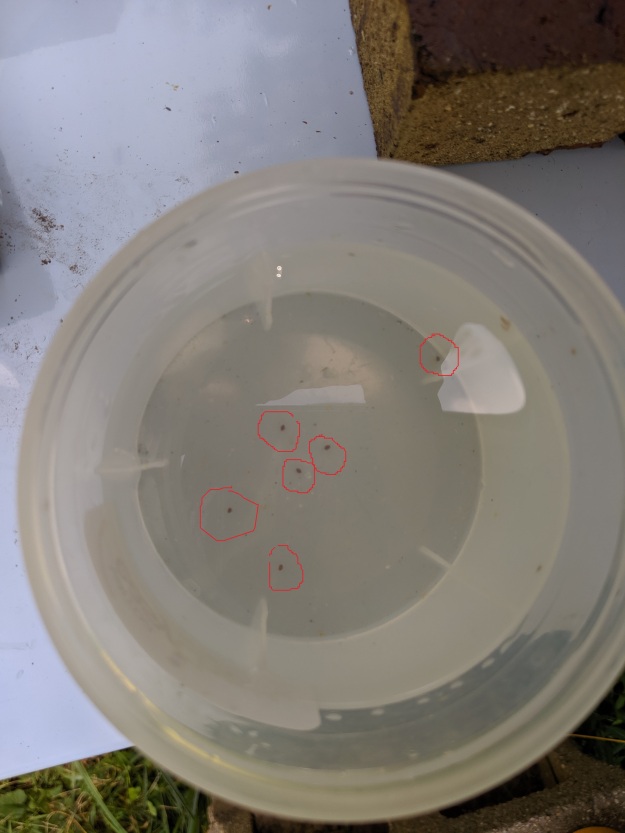

We measured 6 mites, which I circled in red for ease of viewing.

We counted six mites from our sample of approximately 300 bees for an infection rate of 2%. A 2% infection rate is near the threshold for treatment, so we will treat our bees. We only tested one colony even though we have eight colonies. If the infection rate is 2% in the largest, strongest colony, we expect infection rates to be similar or worse in the neighboring colonies.

The next decision a beekeeper has to make is how to treat the bees for varroa mite. Numerous treatments are available, and each one has advantages and disadvantages. Some treatments are organic and can be used while honey is being collected, but other treatments are not. The Honey Bee Health Coalition compiled a fantastic tool to help beekeepers decide the best treatment to use based on how you answer a series of questions. You can find the tool here. We have decided to use formic acid this year. Formic acid is an organic treatment safe for use while collecting honey. Last year we used Apivar strips, which contain the miticide Amitraz. The Apivar strips were effective, but I would like to try to an organic approach this year. We will perform the alcohol wash test again post treatment to measure the effectiveness of the formic acid.

Now is the time of year that beekeepers really need to be thinking about varroa mite control. You need healthy bees going into fall and winter. Ignoring the problem hurts your bees and the bees of the beekeepers around you. People can decide to do nothing and let evolution run its course, but without intervention the evolutionary course seems to be the extinction of the European honey bee. That may be a controversial statement, but that’s the beauty of a blog. You get to write your opinions.

Look for the next blog post where I write about how we recently move two of our hives to a new location so we can establish a second apiary.

Here comes relief:

https://www.ndr.de/fernsehen/sendungen/45_min/Unsere-Bienen-Rettung-in-Sicht,sendung890312.html

LikeLike

Make sure you follow the formic acid treatment instructions to the letter. Some beekeepers report queen losses after treating with formic acid, it’s organic but also powerful stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. We have not used formic acid before, so we are grateful for the advice.

LikeLike

https://www.ndr.de/fernsehen/sendungen/45_min/Unsere-Bienen-Rettung-in-Sicht,sendung890312.html

LikeLike

Bitte nicht blöde bleiben.

Einfach

https://www.ndr.de/fernsehen/sendungen/45_min/Unsere-Bienen-Rettung-in-Sicht,sendung890312.html

lesen.

LikeLike

Pingback: Bee Chemotherapy – Part I | Married with Bees

Pingback: Bee Chemotherapy – Part II | Married with Bees

Pingback: My Thoughts on Murder Hornets | Married with Bees