Have you noticed that whenever things don’t work out the way people want people frequently say, “Well, at least I learned a lot.” “I learned a lot,” is a nice code phrase that lets people know that things didn’t go well at all but you are either choosing to be optimistic or you don’t want to share your problems with the world. In Part I, I discussed how Doug and I were treating our bees with formic acid to lower the varroa mite levels. In case you were wondering how things went with the treatment, all I can say is: “Well, at least we learned a lot.”

We carefully followed the instructions for use of the formic acid. The queen in one of the eight hives we treated died during treatment. I have read that this is a potential side effect of formic acid treatment. It didn’t help that after the first several days of the treatment period we had some days with temperatures above 85 degrees F. When Doug opened the queenless hive to remove the formic acid pads, he saw numerous queen cells and drones. We opted to give the hive another week and check it again to see if the colony made a new queen. Even though fall is here, the weather has been summer like. Maybe the bees could pull off making another queen even though it is late in the year. When we checked again, there was no queen, no brood, and a dwindling number of bees. The frames were full of pollen and nectar. Given that we are now in October, we opted to combine the queenless colony with another colony using the newspaper method. The newspaper method is used to give the bees from the two colonies a chance to “get to know each other” so the new bees won’t attack the queen. You stack the hive boxes on top of each other and separate the old hive from the new hive with a sheet of newspaper. In the time it takes for the bees to work their way through the paper, they should be acclimated to one another. This is a commonly used method especially when beekeepers combine colonies in the fall to increase the bees’ chances of surviving the winter. Unfortunately we did not know that you should not use this method during hot weather because the bees above the newspaper can’t get outside for ventilation. Who knows what we are going to find when we check our combined hive this coming weekend. If the combination of hives didn’t work, “at least we learned a lot.”

The queenless hive wasn’t even the biggest problem. I did another alcohol wash to measure the varroa mite level post treatment. You may recall that the mite level prior to treatment was 6 mites were half cup of bees, which is an infection rate of ~2%. (If you don’t recall, you can check out my previous post here.) That percentage is just at the threshold for treatment. We treated the bees approximately two weeks after that first measurement. We tested the varroa mite levels again about a week after treatment. That means the before and after measurements were about five weeks apart. Guess what…..The infection rate was still 2%.

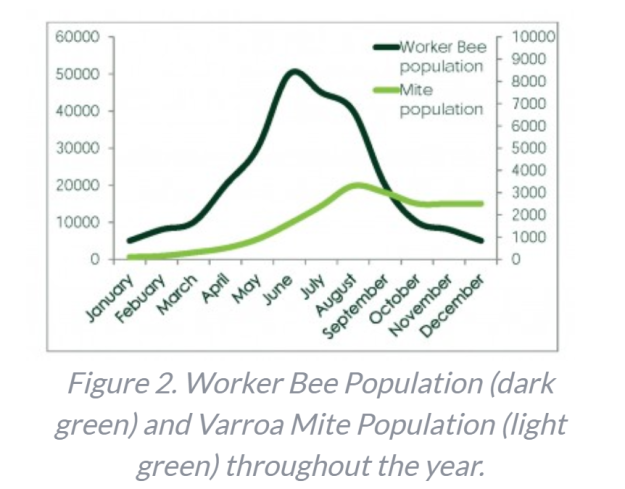

Did the treatment not work? Did we use the wrong treatment? Did we lose one of our queens for no reason? These questions all ran through my mind. We can’t say the treatment didn’t work. The treatment may have worked because this is the time of year when the population of the bee colony declines and the population of varroa increases. (See the figure taken from “Winter Bees and Formic Acid: Used Right, A Successful Combination” by Ulrike Lampe. July 21, 2015 issue of Bee Culture. I didn’t ask the publisher for permission to share the figure in my blog, but hopefully they won’t mind since I cited their work and make absolutely no money from my blog.)

I belong to several local beekeeping forums on Facebook. Several beekeepers complained this year about mite counts being the same or even higher after they treated their bees. Many of these beekeepers were treating with oxalic acid instead of formic acid. One beekeeper noted that the mites may just be particularly bad this year.

I belong to several local beekeeping forums on Facebook. Several beekeepers complained this year about mite counts being the same or even higher after they treated their bees. Many of these beekeepers were treating with oxalic acid instead of formic acid. One beekeeper noted that the mites may just be particularly bad this year.

Knowing which mite treatment to use can be difficult, and there are pros and cons to each treatment. I don’t think we made the wrong decision to use formic acid. I read really good things about formic acid for varroa mite control. Formic acid is more convenient than oxalic acid, which has to be vaporized in the hive. Apivar worked great for us last year, but I have read that mites are starting to become resistant to miticides, and you need to rotate treatment methods every two years if you are using a miticide.

The big decision we need to make is whether or not we should treat our bees again before winter with an alternative agent such as Apivar. I asked around at my local bee club meeting and got mixed answers. I also asked the Kentucky Beekeepers group on Facebook. One of the beekeepers painted a very gloomy picture stating our bees may not make it through the winter because this is so late in the year to have mites.

Doug and I have very different opinions about what to do next. Doug and I will celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary in December. When we married, Doug was the carefree one and I was the one who was concerned about everything. We were a good balance for each other. Sometime around year 17 or 18, we both gradually switched roles. I became much more easy going, and Doug became the one concerned about everything. The change caught us both by surprise, but we were still a good balance for one another. In year 24, we started to switch roles again. I am convinced that our bees are in trouble and we will suffer hive losses this winter. Doug thinks our bees are doing great and that we will get all seven hives through the winter. The bees have loads of honey and pollen since we didn’t take any honey this year. (You can read all about our secret shame here if you missed it.) Doug says that it is unrealistic to think we will get the varroa mite load to zero. He also thinks that treating the bees again by any method will stress the bees and do more harm than good. Do we give some of the hives another treatment, or go with an all or nothing approach? If any beekeepers want to comment, I would love to hear from you.

Beekeeping has no guarantees. As one of my friends in the local bee club said, “You shouldn’t be a beekeeper if you can’t handle death.” I am keeping my fingers crossed that we have done what is right for our bees and that we can keep away the grim reaper for another year. If the grim reaper comes for our bees, we will tell people, “Well, at least we learned a lot.”

We do have varroa here in the UK but I’m not sure we worry about it quite so much. I practice mite control with open floors, drone comb removal and an apiguard treatment in late summer. I would be more worried about winter losses through damp or starvation and that’s where I put in the effort. I tend to agree with your hubby. Fingers crossed!

LikeLiked by 1 person